The fundamental problem with “network neutrality” rules aptly is illustrated by Apple’s talks with Comcast about enabling an Apple set-top box that has assured quality of service on Comcast’s high speed access network.

In other words, Apple does not want “best effort access,” which is what network neutrality mandates. Instead, Apple wants a managed service with quality of service controls.

Some immediately will note that what Apple wants is not "packet prioritization" of the type forbidden by network neutrality rules.

But some will say the nomenclature is a bit of a ruse.

To wit, Apple does not believe “best effort” is good enough to ensure the quality of its proposed streamed content, and wants to be provided as a managed service over Comcast's access network.

To be sure, the Federal Communications Commission specifically exempts such managed services from the network neutrality rules.

But some will note the irony: an IP app a "managed service" is lawful. An over the top Internet app cannot use priority delivery mechanisms.

If Apple succeeds, you can be sure a wave of new "managed services" will be created, using prioritized access.

One immediate question is what is required for a service to be considered a "managed service," not an over the top Internet app. On the face of it, it would seem to be the offering of such a service by an Internet service provider directly, much as telcos, cable companies and satellite providers sell "managed" voice service or linear video entertainment.

In other words, "who owns the service" might well become the clear delineation.

That also suggests lots of opportunity for future business deals between over the top and ISP partners to create such managed services. In large part, that would render "network neutrality" a bit more hollow.

Such "who owns the service" regulation is one reason many have supported “network neutrality;The whole point of such a framework was to prevent ISPs from favoring "their own" apps over similar offerings provided by independent third parties.

The potential Apple deal with Comcast would increase the uncertainty about the soundness of the framework long term.

Few would question, at least at this point, the "right" of a facilities-based access service provider to create its own branded managed services.

That is what voice service is, after all.

Likewise, nobody would question the right of a TV or radio broadcaster, telco, cable company or satellite services provider to create and deliver a service over its own network.

The big issue has been the framework for over the top, unaffiliated apps and services.

The Apple proposal gets around that issue because the proposed streaming service essentially would be a service created and "owned" by the access provider (even if Apple is the essential partner).

There are some trade-offs for the video service supplier. It might mean such a managed service is not available as an Internet app, only as a for-fee service offered by one or more ISPs.

That will limit potential audience to a certain extent, unless the managed service reaches agreement with most of the ISPs in a market that represent 80 percent to 90 percent of the potential customer base.

The enduring issue is that quality delivery of paid-for video entertainment is subject to the same congestion issues that cause video stalling as all other apps when access networks are congested.

In seeking to become a managed service, Apple wants priority delivery of its video bit, the very sort of thing network neutrality advocates have opposed.

But that is the fundamental problem with network neutrality, some would argue. Prioritized access, under conditions of congestion, is a surefire way to deliver the bits with higher end user value.

Consumer welfare, in other words, is increased when consumers get priority delivery of apps that are highly susceptible to degradation when access networks are congested.

Apple’s efforts essentially are a rebuke to the notion that network neutrality actually enhances consumer welfare.

It is one thing to argue that all lawful apps should be accessible to any user of the Internet. Everybody agrees on that point.

The Federal Communications Commission, furthermore, already has adopted “no blocking” as a fundamental principle.

But priority delivery is not blocking. It is a mechanism for providing quality of service when networks are congested. It’s the same principle as all content delivery networks lawfully use.

Apple wants its video streaming traffic managed, not delivered “best effort,” as is Comcast Internet traffic; in other words, to have its service offered as a managed service, not an “Internet app,” as Comcast’s linear TV also is treated.

Precisely how regulators might view any future service of this type is not clear.

The FCC already exempts “managed” services from the “best effort only” network neutrality principle.

The important observation is that Apple is pointing out why prioritized access (even when it is called something else) is so important for voice and video apps, and why “best effort only” is not an optimal solution for delivering applications highly dependent on stable and predictable bandwidth.

Monday, March 24, 2014

Apple Wants Priority-Assured Video Services Delivery

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Why "Cloud" is Strategic for Capacity Providers

“Cloud” is a key business concept and the underpinning of revenue growth strategy for capacity providers, not simply a new computing architecture for app providers.

Simply, revenue growth hinges largely on serving the needs of content providers and data centers serving content providers. Content demand now drives the places bandwidth has to be supplied, why it has to be supplied, and therefore where transport revenues can be earned.

And those are some of the ways “cloud computing” is shaping transport provider revenue opportunities.

Simply, revenue growth hinges largely on serving the needs of content providers and data centers serving content providers. Content demand now drives the places bandwidth has to be supplied, why it has to be supplied, and therefore where transport revenues can be earned.

Instead of networks optimized for moving symmetrical narrowband traffic from one telco point of presence to another telco point of presence, the long-haul networks now mostly move asymmetrical broadband traffic from one data center to other data centers.

That shift to “east-west” (server to server) traffic, from “north-south” (client to server) is shaping demand for capacity, and therefore revenue, with a big role played by end user demand for content, and hence for content delivery networks.

About 51 percent of all Internet traffic will cross content delivery networks in 2017 globally, up from 34 percent in 2012, according to Cisco. And since much of that content is high-bandwidth entertainment video, CDN-related traffic flows now are crucial for transport services providers.

The other big change wrought by cloud-based content apps is dramatic change in the geography of demand.

In fact, Cisco estimates, metro traffic volume will surpass long-haul traffic in 2014, for example, and will account for 58 percent of total IP traffic by 2017.

In fact, metro network traffic will grow nearly twice as fast as long-haul traffic from 2012 to 2017, Cisco argues. And much of that traffic will consist of video.

Globally, IP video traffic will be 73 percent of all IP traffic (both business and consumer) by 2017, up from 60 percent in 2012.

Cloud architecture has other implications for transport providers, namely the way cloud-based apps are “assembled,” rather than simply served up whole to requesting users. That is one reason why east-west traffic is growing.

Transport provider revenue growth increasingly is driven by supporting customers needing to move large amounts of content--especially video--from one data center to another, to assemble full apps or pages served up to end users.

In fact, the bulk of global undersea traffic arguably now consists of video-based Internet applications, hosted from huge data centers. One way of describing such east-west traffic flows is that traffic moves between servers, not between an end user and a server.

Though the actual application the end user uses is a communication north-south (client to server), often much of the “app” gets assembled from multiple servers.

And those are some of the ways “cloud computing” is shaping transport provider revenue opportunities.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Friday, March 21, 2014

Twitter Cutoff in Turkey is What Blocking Really Looks Like

Twitter was blocked in Turkey after Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan objected to tweets critical of his government. That is what app blocking really looks like.

Network neutrality, by way of comparison, concerns only the preservation of "best effort only" levels of Internet access by consumer customers.

Network interconnection, or Internet domain interconnections, which some want to drag into the network neutrality framework, also is not "blocking" of lawful apps.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

E-Commerce is a Winner Take All Market, So Far

Another example of “winner take all” economics in Internet-based content, e-commerce and advertising markets, where a few giant competitors rule the market.

Amazon is larger than the next dozen largest e-tailers combined. That same sort of effect can be seen in mobile advertising, over the top video entertainment, and is developing in over the top messaging.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Average U.S. Internet Access Speeds Double in 3 Years

Average U.S. Internet access speeds have doubled in just three years, according to Broadband for America.

IN 2010, the average connection speed in the United States was 4.7 Mbps. In the third quarter of 2013, the average connection speed had more than doubled to 9.8 Mbps. while the average peak connection speed was 37.0 Mbps.

Rapid increases, despite some sense, in some quarters, that change is not rapid enough, have been quite rapid, indeed, in large part because of retail offers from cable companies.

The standard cable broadband speed has increased 900 percent since 1999.

In August 2000, only 4.4 percent of U.S. households had a home broadband connection, while 41.5 percent of households had dial-up access.

A decade later, dial-up subscribers declined to 2.8 percent of households in 2010, and 68.2 percent of households subscribed to broadband service.

In other words, from 2000 to 2012, the typical purchased access connection grew by about two to three orders of magnitude in about a decade.

If that continues, gigabit connections will be common within two decades.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

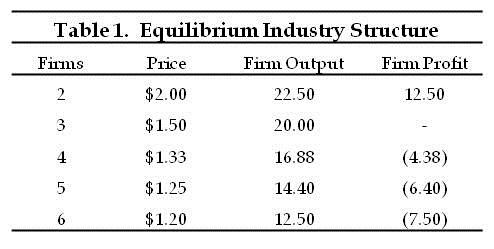

Do French and U.S. Mobile Markets Have Too Many Competitors?

Does the U.S and French mobile business have “too many” or “too few” contestants? And no matter which view is taken, on what basis are informed judgments made?

Consider the rival bids being made by Altice, owner of French cable concern Numericable, and Bouygues, a leading French mobile operator, for the assets of Vivendi’s SFR mobile business.

In the wake of a decision by SFR to negotiate exclusively with Altice, Bouygues had been expected to pursue a merger with Iliad, which owns France's fourth mobile operator, Free Mobile.

Observers say regulatory risk is an important element of SFR thinking. A Bouygues purchase of SFR would reduce the number of national mobile providers from four to three, while French regulators prefer a minimum of four providers.

In that view, a purchase of SFR by a cable company would be preferable to reducing the number of mobile service providers. Of course, some would argue the mobile segment currently has too many contestants for a stable, healthy, longer term market that remains competitive.

In the U.S. market, Sprint has been sounding out regulators about a potential bid by Sprint to acquire T-Mobile US. By all accounts, U.S. Federal Communications Commission and antitrust authorities at the Department of Justice are skeptical about such a potential merger.

The reasons fundamentally are the same as in France: regulators have more confidence in a four-player market than a three-provider market, in terms of maintaining robust competition.

The problem is that there is no way to know, in advance, which position--the market is too concentrated, or the opposite market is not concentrated enough--is correct, in terms of maintaining both robust competition and also incentives for continual investment.

In fact, globally, a “rule of three” already seems manifest. That is to say, in any mature industry, three suppliers dominate the market. Of 40 major markets studied by mobile analyst Chetan Sharma, the top three mobile operators controlled 93 percent of their respective markets.

In some “hyper-competitive markets” like the United Kingdom and the United States, “which had more than four to five large players” are moving towards the consolidation phase where the top three control more than 80 percent of the market, Sharma has said.

Opponents of a Sprint acquisition of T-Mobile US argue that consumer retail prices likely will rise, in the event of a merger. Indeed, that is one reason why most equity analysts think only such a merger will end the current price war in the U.S. mobile market.

Economists and analysts at the Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal and Economic Policy Studies agree that retail prices likely would rise in the wake of a Sprint acquisition of T-Mobile US, but also argue that isn’t the point. Even higher retail prices do not tell the long-term story about sustainable levels of robust competition and sustainable incentives for continued investment.

Though it sometimes seems counter-intuitive, retail prices that are too low necessarily drive weaker competitors out of the market, leading to more market concentration. Prices that are too low also dissuade contestants from investing aggressively, as there is little to no profit for doing so.

But the issue is whether any regulatory bodies, anywhere, are smart enough to know, in advance, whether consumer welfare outcomes are better with three or four national providers.

Economic theory suggests “excessive competition” can lead to negative profits, and therefore death, of all contestants in a market with too many competitors. Consolidation is the inevitable result.

And, one might well argue,, such consolidation provides a better outcome for consumers.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

Winner Take All Markets Have Clear Business and Regulatory Implications

Some would point to modern retailing and the rise of Wal-Mart as one example of a winner take all market.

Many would say the music industry, and digital information or content businesses, increasingly take on a “winner take all” character. Some argue that is true in large part because information technology now allows any single firm to reach huge markets, affordably, compared to what was possible in the past.

That means the very best supplier in any industry affected by economies of scale--and that is most industries these days--will do disproportionately well.

Some might argue “winner take all” economics easily can arise in industries where fixed cost is high and marginal costs are low.

If that sounds familiar, it is because that is the structure of the global telecom business as well. “Winner take all” might be expressed as the “rule of three,” describing the typical national telecom market which is dominated by no more than three providers.

One example is the new concentration of revenue in the mobile advertising business.

For observers long accustomed to the relative fragmentation of advertising revenues and market share across television, radio, newspapers and magazines, the extreme concentration of mobile advertising revenue is shocking.

Facebook and Google accounted for about 67 percent of all global mobile ad market revenue in 2013, and it is projected that Facebook and Google will earn nearly 69 percent of all global mobile ad revenue in 2014.

Between them, Google and Facebook earned 75 percent of the $9.2 billion in incremental global mobile ad revenues in 2013 ($6.92 billion), according to eMarketer .

That's one example of a "winner take all" market. Of course, there are implications for regulators responsible for oversight of communications markets. To the extent the theory holds, only a few firms will dominate every telecom market, eventually.

That tendency to "fewness" will be relevant in coming days as much of the global communications business consolidates. The point is that, no matter what, a truly competitive market will eventually consolidate into leadership by just a few companies.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Costs of Creating Machine Learning Models is Up Sharply

With the caveat that we must be careful about making linear extrapolations into the future, training costs of state-of-the-art AI models hav...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

Who gets to use spectrum, and concerns about interference from other users, now appears to be an issue for Google’s Project Loon in India. ...